AMHP efficiency and Jevons paradox

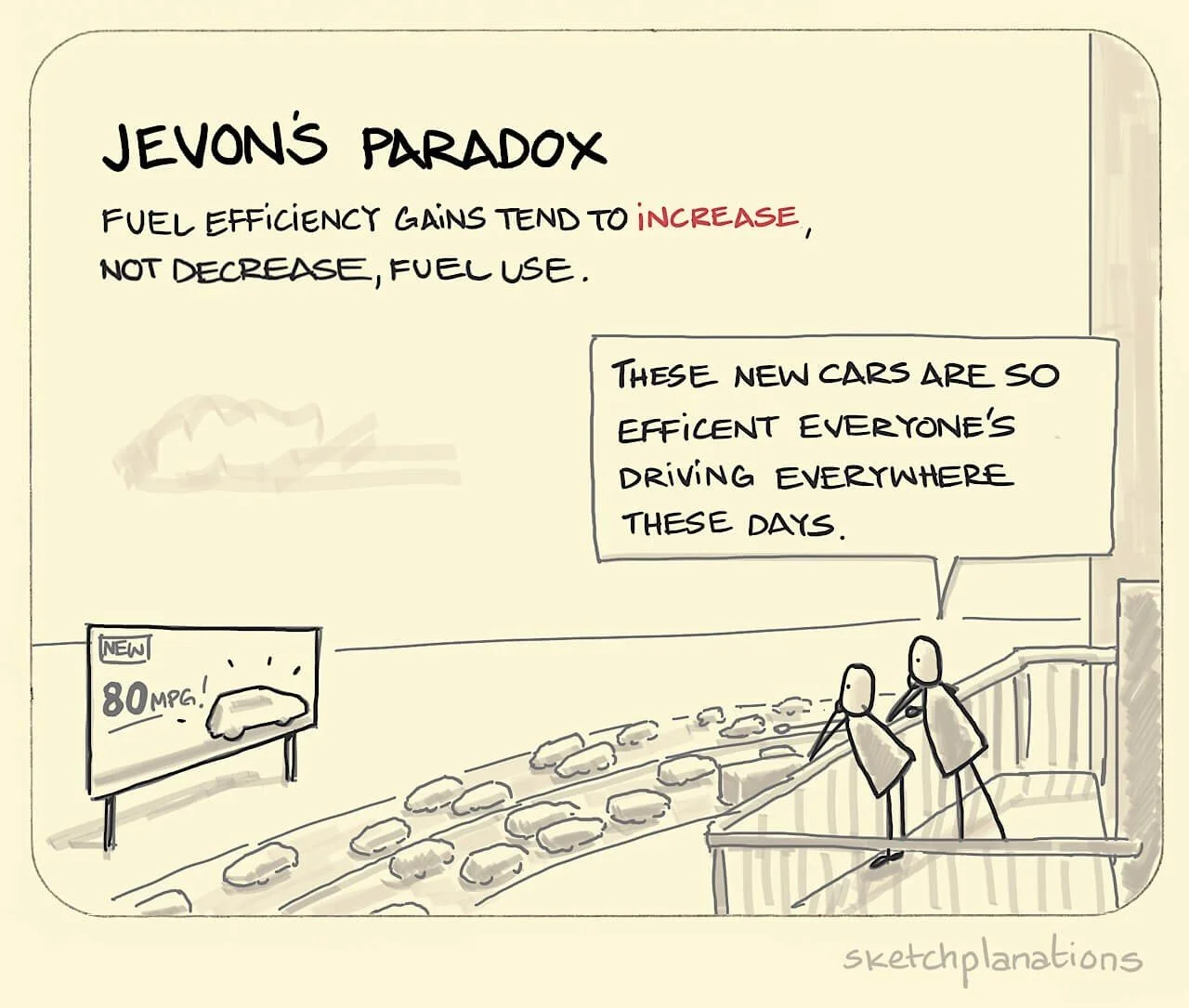

Image: Jono Hey, Sketchplanations. Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International License.

By Jamie Freeman

The recent release of the Chinese AI chatbot DeepSeek caused some significant waves in the tech industry, not least because the market value of American tech companies plummeted. DeepSeek has seemingly upended many of the assumptions regarding the resources and funding required to produce the next generation of AI. Drawing parallels with the US-USSR space race, many observers described it as AIs sputnik moment (Milmo et al. 2025; Roose and Newton 2025). Amidst the panic however, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella attempted to put a positive spin on the situation by referencing a 160-year-old economic theory; Nadella posted on social media “Jevons paradox strikes again! As AI gets more efficient and accessible, we will see its use skyrocket, turning into a commodity we just can’t get enough of.”

Now, I’m no AI nerd. Nor am I an economist. I was certainly not aware of William Stanley Jevons 1865 work titled The Coal Question. What felt interesting however, was the paradoxical idea that efficiency can actually increase, rather than reduce demand. Jevons paradox then, might be a useful framework to examine the AMHP role, including its organisation and operation.

Jill Hemmington (2024) recently highlighted the growing dissonance between two different approaches to AMHP practice. On the one hand, you have AMHP work viewed through the lens of a technical-rational endeavour. Work is process driven and legalistic. The occupational context is efficiency and the culture is managerial. Hemmington (2024) depicts a macho/military culture which is driven by the ‘need for speed’ and the pressure of ‘Just Fucking Do It’ (JFDI). On the other hand, there is AMHP work which is seen as an ethical and moral undertaking, and more closely aligned with relationship-based practice. This is exemplified by AMHPs who ask the reflexive question ‘Who are we for’? (Hemmington 2024). My feeling is that this is a not a binary state but rather a cultural or dialectic tension, which permeates through organisations, teams, and individuals. I think that most AMHPs can relate to this tension. Personally, I think about the tension between my academic training and Local Authority placement. This is what you learn but ‘this’ is what you do. I also reflect on how my own practice bends with time pressures. For example, my ability to “consider the patient’s case” (s.13(1) MHA) feels compromised when I am juggling two, three, or more referrals. I can also observe this tension in the context of AMHP hubs. Whilst I haven’t worked in an AMHP hub, this model, viewed from afar, seems to be the epitome of efficiency and AMHP as administrator. For my part, increasingly I am packing this tension away somewhere towards the back of my mind. It is labelled ‘the AMHP I want to be vs. the AMHP I inevitably am’. This friction is my moral distress (Hemmington 2024). The friction between my actual AMHP practice (‘the is’) and where I would like my practice to be (‘the ought’).

I think that Jevons paradox can be a useful framework to interrogate this further. During the mid-19th Century, William Stanley Jevons was establishing the foundations of neoclassical economics by applying mathematical and statistical methods. In 1865, Jevons examined industrial concerns about coal shortages in England. It was broadly accepted that coal shortages would be averted by various technological innovations which were making coal consumption more efficient. Jevons argued, however, that energy efficient technology would, paradoxically, increase coal consumption. He wrote “It is wholly a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to a diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.” (Jevons 1865 p.103). Although Jevons made a number of important contributions to economics, Jevons paradox was largely forgotten about until the 1970s when early ecological economists revisited his ideas (Shanahan 2022). In environmental policy, it is often described as the rebound effect (Vivanco et al. 2016). This is seen when technological advances create energy efficiency and reduce environmental impacts. However, as costs become lower, consumption increases, and environmental gains are lost or mitigated. A classic example concerns fuel efficiency and passenger cars. Rather than reducing consumption, fuel efficiency has made car travel cheaper. People now tend to use their cars more often and travel greater distances. Additionally, people now often buy second cars or bigger cars, or they spend these savings on other environmentally damaging products (Vivanco et al. 2016). The rebound effect is a lost-benefit formula [(efficiency – saving)/10]. For example, if a car is 20% more efficient but fuel use for that car only declines by 15% there is a 50% rebound effect. Jevons paradox occurs when there is an increase in consumption and the rebound effect is more than 100%. Jevons paradox has been observed across multiple scales and contexts (York and McGee 2015).

As far as I am aware, Jevons paradox has never been empirically examined in health and social care settings. Anecdotally however, it was discussed in a recent Planet Money podcast, examining why doctors still use their old-fashioned pagers (Guo and Fountain 2023). Mary Mercer and Christopher Peabody, two San Francisco doctors, looked at ways of improving efficiency in their emergency department and quickly settled on the idea of replacing their antique pagers with a doctor-version of WhatsApp. They completed a trial and were surprised when it failed miserably. The ED doctors quickly became overwhelmed by the quantity of messages. In reflecting on this, they realised that taking the time to page a doctor was seen as a serious step. Sending them a quick text message, less so. The doctors were quickly bombarded with messages, photos, and videos from their emergency department colleagues, seeking a little advice, a quick answer, or speedy diagnosis. Amid all the noise, the doctors quickly began to ignore the new technology. Eventually, they would only respond to their pagers. Tim Harford (2024) later pointed out the parallels in this experiment with Jevons paradox. Whilst texting was much more efficient, the demand was so overwhelming that the ED doctors opted-out.

In the context of AMHP practice, Jevons paradox might be viewed as an important and cautionary tale. Neoliberal government agendas and austerity politics create conditions that prioritise efficiency and value for money. There is an increasing pressure to do more with less. AMHP teams can be and are streamlined according to a process of screening -> MHA assessment (in the traditional AMHP and two doctor sense). Colleagues working in large AMHP hubs, for example, describe waiting for their MHA assessment to be allocated before they race to recruit s.12 doctors. This technical-rational operation can be slick and efficient. Organisations can pat themselves on the back as they clear the referral board. From a personal perspective, we might actually get home in time for tea. Colleen Simon describes this as the ‘sausage factory’ where there is often considerable pressure to get people assessed (Ruck Kenne et al. 2024). In this context, I think that AMHPs can also end up operating in a much more process driven way. It is easier, and faster, to think in terms of criteria. I might feel more certain (and less anxious) if I categorise patients as detainable/not detainable, for instance. We might also see the evolution of this efficiency through the prism of external pressures and systems anxiety. Efficiency soothes anxiety. And amid the uncertainty, process is reassuring. However, we might also pivot, and ask ourselves again, who are we doing this for? Is my practice aligned according to the needs of the system, crumbling mental health services, my organisation or team, my colleagues, or the patient who is at risk of losing their liberty? The late Matt Simpson very articulately advocated for the MHA assessment before the MHA interview under s.13(1) MHA (Simpson 2024). And this is further explored in the excellent discussion paper ‘MHA Assessments’ and s.13(1) MHA 1983 (Simpson et al 2024). Matt recognised that “such assessment activity requires the investment of time…” (Simpson 2024 p.810) to prioritise transparency, connection, and collaboration with patients, their families, and other professionals. This is the idea of “changing gears and buying time” (Simpson 2024 p.812). Driving in a lower gear is not very efficient, but it can be important when navigating down a steep hill. Time creates the space for alternatives, particularly opportunities to achieve less restrictive practice. This is the AMHP as considerer or the considerate-AMHP. There are opportunities at each stage to prioritise collaboration and allyship with the patients and families that will be impacted by my decisions. The pressures remain. Risk (real, imagined, exaggerated) and uncertainty often fuel the pressures which culminates in the JFDI mindset and cultures. There is familiarity and certainty at the end of a traditional MHA assessment. But who does this soothe?

Jevons paradox also teaches us that there is a significant risk that if we continue to prioritise efficiency, we are also likely to increase demand, akin to those San Francisco doctors who were migrated over to doctor-WhatsApp. Alarmingly though, unlike the doctors who collectively begun to ignore their messages, we are answering them. In this way, I suggest that AMHP services which are organised around the traditional MHA assessment, are likely to receive more and more referrals. There is a real danger that this creates a negative feedback loop. More referrals, more assessments, and more patients being detained. We are bumping up against resource pressures, of course. Most obviously inpatient beds. However, are we also contributing, as the MHA gatekeepers, to a broken system of churn and repeated admissions? I believe that we must move towards the idea of the considerate-AMHP. We need to develop and nurture the professional skills to tolerate the uncertainty that comes with this standpoint, and role model this among our colleagues. Collectively we might pause. We should consider how our organisational context is supporting us, and to what end. On an individual level, it can feel like there is considerable pressure to ‘get it done’. For example, all my considering, might feel like it is adding to the pressure on my colleagues and the team. However, over the long term, might I actually be reducing demand, as well as achieving better outcomes for patients exposed to the MHA. I was recently talking with one of my experienced AMHP colleagues, who described their career as “more than just a job”. Bringing their best practice over the long term, has required time and commitment. This is considered, deliberate, thoughtful, and unapologetically inefficient. In a world that insists that we do more with less, AMHPs might confidently occupy the uncertain spaces and attempt to reclaim our greatest resource – time.

References

Guo, J. and Fountain, N. 2023. Why do doctors still use pagers? [Podcast]. 8 December 2023. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2023/12/08/1197955913/doctors-pagers-beepers

Harford, T. 2024. There is no need to lose our minds over Jevons paradox. Financial Times [online]. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/22b8e5f1-732e-4cbd-acb0-9990f63f659e

Hemmington, J. 2024. Approved Mental Health Professionals’ Experiences of Moral Distress: ‘Who are we For’? The British Journal of Social Work, 54(2): 762 – 779.

Jevons, W.S. 1865. The Coal Question. An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal Mines. London: Macmillan.

Mental Health Act. 1983. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1983/20/contents

Milmo, D, Hawkins, A, Booth, R. and Kollewe, J. 2025. ‘Sputnik moment’: $1tn wiped off US stocks after Chinese firm unveils AI chatbot. Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2025/jan/27/tech-shares-asia-europe-fall-china-ai-deepseek

Roose, K. and Newton, C. 2025. Your Guide to the DeepSeek Freakout: an Emergency Pod. [Podcast]. 28 January 2025. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/27/podcasts/your-guide-to-the-deepseek-freakout-an-emergency-pod.html

Ruck Keene, A, Simon, C. and Mitchell, J. 2024. AMHPs, MHA admission and changing cultures – in conversation with Colleen Simon and John Mitchell. [Shedinar/Podcast]. 3 October 2024. Available from: https://www.mentalcapacitylawandpolicy.org.uk/amhps-mha-admission-and-changing-cultures-in-conversation-with-colleen-simon-and-john-mitchell/

Simpson, M. 2024. Changing Gears and Buying Time: A Study Exploring AMHP Practice Following Referral for a Mental Health Act Assessment in England and Wales. The British Journal of Social Work, 54(2): 797 – 816.

Simpson, M, Lewis, R. and Mitchell, J. 2024. ‘MHA assessments’ and s13(1) MHA 1983: ‘New’ AMHP practices within existing law. A discussion paper. [E-book]. Available from: AMHP Leads Network - Resources Page

Shanahan, E. 2022. Herman Daly, 84, Who Challenged the Economic Gospel of Growth, Dies. The New York Times [online]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/08/business/economy/herman-daly-dead.html

Vivanco, D.F., Kemp, R. and van der Voet, E. 2016. How to deal with the rebound effect? A policy-oriented approach. Energy Policy, 94: 114 – 125.

York, R. and McGee, J.A. 2016. Understanding the Jevons paradox. Environmental Sociology, 2(1): 77 – 87.